Pluto in Aquarius: Too Big to Fail, Too Inhumane to Succeed

The last time Pluto was in Aquarius was the French Revolution. I took a class on the revolution in college and heard this heartbreaking story: The peasants were on the side of the monarchy for a long, long time, even though they had the most to lose.

They said, “If only the king knew what was happening, he would fix it.”

They had no idea the king didn’t know or care about them. They were still living in a feudal mindset, believing that loyalty went both ways, long after the world moved on.

I was reminded of this story a few years later when I went to visit family in Pittsburgh. They took me to a seminary that had set up shop next to an old factory. The school wanted to build classrooms in the old, crumbling building next door, but the city refused.

“If only the steel company knew what happened to our town after they left, they would come back and fix it,” they said.

They remembered the days when big corporations invested in the local community, building housing for workers, an excellent medical system, and a university. So, the building sat empty, waiting for the companies to return like England waiting for Arthur and the French peasants waiting for the ear of the king.

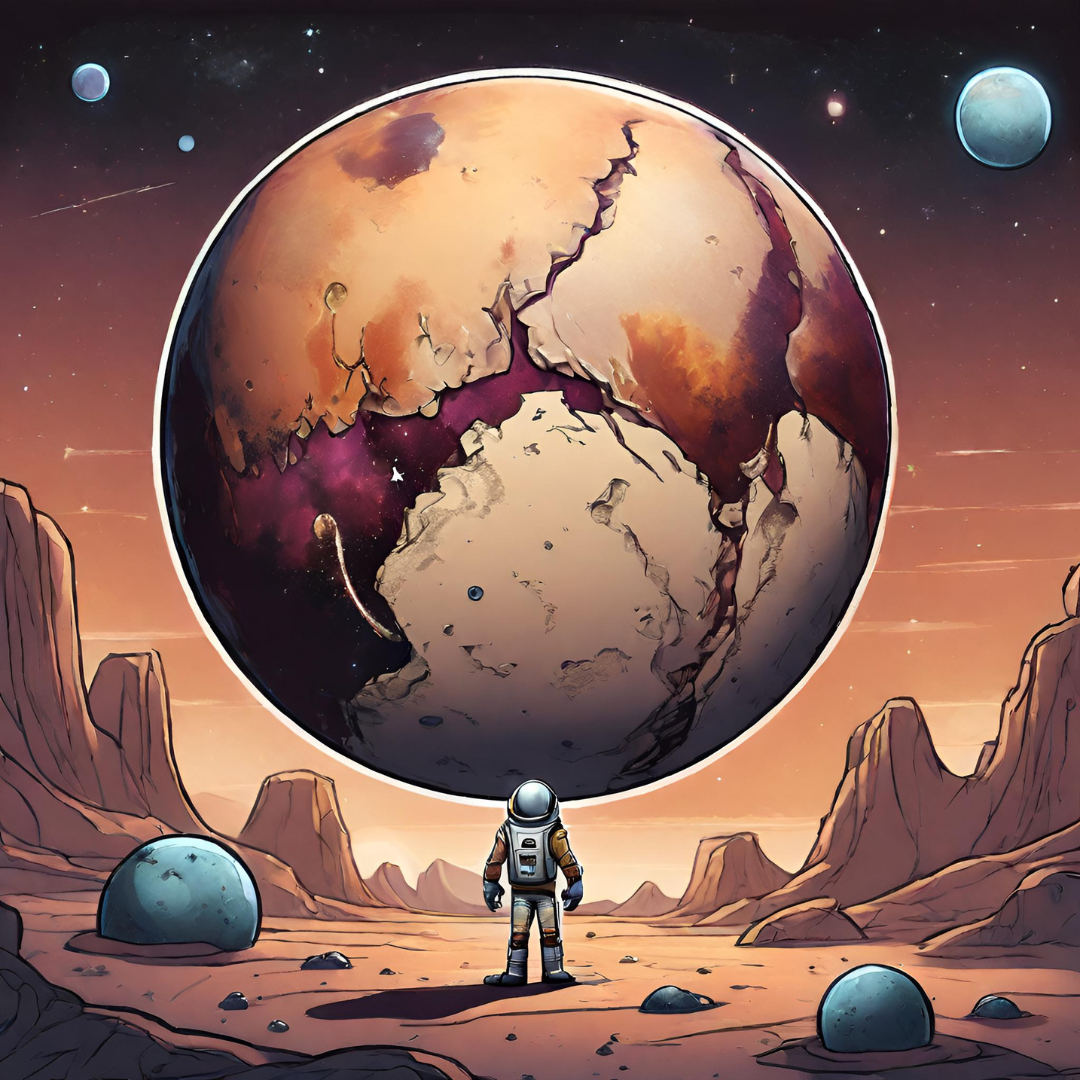

Pluto in Aquarius shows us the structures that are too big to fail but too inhumane to succeed. Last time, the story ended with the birth of empires. This time, we are watching the last vestiges of empires collapse.

When I moved from Boston to Berkeley in 2009, my friends and family teased me. “What is the matter with you,” they said, “You’re moving three thousand miles to go to Cambridge West?”

Since most of my critics were academics, and I was in graduate school, all they could see were two university towns. They had never lived in the West, and they were operating on the assumption that culture could be stretchy enough to reach across a continent, and the land a community lives on has absolutely nothing to do with a people’s way of life.

I quickly learned that there are enormous differences between Boston (“Cambridge East”) and Berkeley (“Cambridge West.”) One spends half the year blanketed in snow and ice, and the other can count on temperatures that hover around 68 degrees most of the year. One was built unmoving granite scraped clean by glaciers. The other was built on an active fault line that cuts through the school’s stadium. One could rely on precipitation roughly every three days. The other cycled between seasons of heavy rain and drought.

Each of these areas of difference had a profound impact on the collective personality of these places. It showed up in their relationship with tradition and innovation, their introversion and extroversion, the rate of change and speed of daily life.

But the most surprising thing about living in a state that prides itself on having a GDP bigger than most countries was how much I felt like I was living in an outpost of the empire.

I first became aware of this frontier feeling during my first wildfire season. The ecosystem in Western North America has evolved to require regular fire cleanses. There are plants that can’t reproduce without it, and the animals and people who thrive here have adjusted to the idea that everything can go up in smoke at a moment’s notice.

Once upon a time, the indigenous people worked with the land’s need for wildfires. They lived lightly. Setting small, contained fires periodically was part of their practice of cultivating the land.

Settlers couldn’t see fire as anything but a tragedy. For generations, it was official government policy to keep fires from happening, so wildfire fuel accumulated in the undergrowth, waiting for a stray spark to set the landscape ablaze.

As a person who spent the first 25 years of my life on the East Coast (before it, too, I am told, started catching on fire) it was stunning to me that wildfire season exists at all, never mind regularly occurring wildfires that cover thousands of acres. A thousand acres is an unspeakably large piece of land to me. A wildfire that size is pretty close to my inner Evangelical’s definition of Hell.

Living through wildfire season isn’t easy. Even if you’re lucky enough to be out of the range of the fires, the air is unbreathable for months at a time. People huddle inside, hiding from the smoke and scorching heat with the windows closed—mostly, in Western Oregon, without air conditioning—while each of a hundred fires devours an area the size of a New England state.

At first, I assumed that a wildfire season that bad must have been an anomaly.

“Have you heard about the fires?” I asked my friends back East.

“No,” they said. “There’s been nothing about it on the news.”

Fire season dragged on. Nothing was reported. I described what it was like, and no one I knew on the East Coast believed me. I watched a town in Central Oregon with the only supermarket for a hundred miles burst into flames. It was barely even mentioned in the Portland news.

I shared my dismay with my local friends, and they chuckled at me.

This is when I learned that the fierce independence of the West comes from the knowledge that, if you’re in trouble, it’s unlikely that anyone will come to help you. The people in charge are far away in capitals you’ll never see and have no idea you or your problems exist. The wildfire season I was observing wasn’t especially notable, and despite the weak bleating of our US Senators, swearing that they were trying to get disaster relief funds from Washington, no one was holding their smoke-filled breath about it.

There was a time when it was expected that an essay like this would be the beginning of a call to expand the circle of our compassion, but one of the lessons I have noted from Pluto’s brief time in Aquarius is that disaster porn can be a form of dissociation. It is easier to hide from your own pain—and the pain of your immediate neighbors—when you can convince yourself that you are doing something helpful by tweeting about a disaster on the other side of the world.

Astrologers disagree about whether or not Aquarius is about community. Some make a connection between Aquarius and the 11th house and talk about aquarians as the original community organizers. Others look at Saturn’s traditional rulership of Aquarius and say that aquarians like to be left alone. Many astrologers hide behind the quip that Aquarius loves humanity and hates people, usually turning away from the horrifying implications of what that really means.

Like I usually do, I am, once again, coming down on everyone’s side. As an Aquarius moon, I say Aquarians are communities organizers, and we like to be left alone, and we have the horrible love of participating in committees that make decisions for abstract populations filled with people we will never know.

I believe that we will see all those faces of Aquarius while Pluto is traveling through that sign, but Pluto is fundamentally a problem-solving planet, so the focus will be on the dilemma of living in systems that are simultaneously too big to fail and too inhumane to succeed.

The answer, I think, will be to remember our most ancient ancestors, the rodent-sized mammals who scratched out a living in the age of the dinosaurs and survived the comet: The easiest way to survive the apocalypse is to carry your own heat and be small and insignificant enough to hide a small city of your people in the cracks.

Related Articles